This post is part of a series about a late antique Egyptian-style tunic project, starting with this overview of the tunic and going into the details about several aspects of the tunic in their own posts. Text references are listed at the bottom of this post; extant artifacts are linked directly to museum catalog pages in their captions.

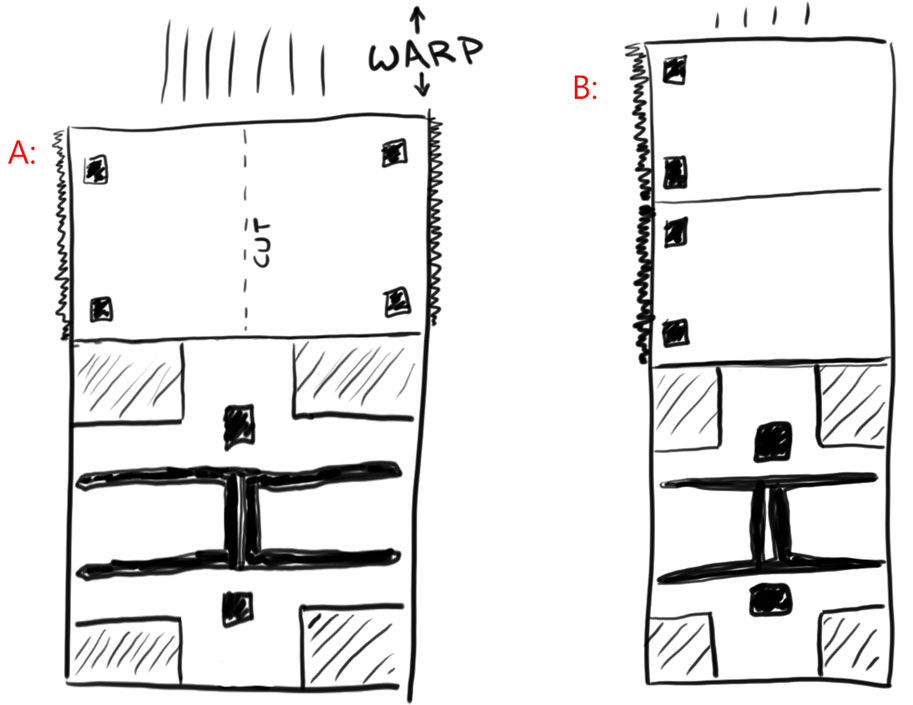

This style of tunic was woven to shape, with sleeves included. It was woven sideways on a wide loom with the sleeves pointing up and down in the same direction as the warp. See South and Kwaspen, 489-490 (tunic type 3); Mossakowska-Gaubert, 322; and Rooijakkers, 176 and 201.

Earlier tunics are made of linen woven in a simple tabby, but wool tunics in bright colors woven in tapestry weave became more common as wool gained in popularity during the Roman/Byzantine periods. (See low frequency of plain linen tunics of this type in South and Kwaspen, 490-493.) The color of my tunic is one that likely would have been executed in wool, but I used linen because it is more comfortable for me in warm environments, and I had this fabric in my stash.

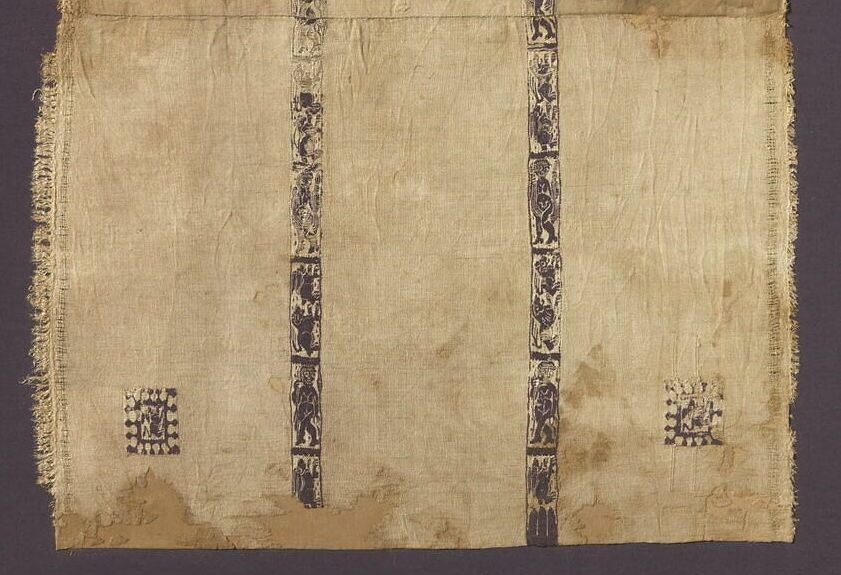

These tunics could be woven in one piece or two/three, depending on the width of the loom. A tunic woven in multiple pieces would have the upper part of the tunic that goes over the shoulders woven as one piece, with neck slit, sleeves, and upper body all together. Then one large rectangle (wider loom) or two smaller rectangles (narrower loom) would be woven, possibly with weft fringe at the selvedge(s). South and Kwaspen, 490; Mossakowska-Gaubert, 333.

A larger rectangle would be cut in half up the center and the cut edge of each half attached to the upper body piece where the seam could be hidden and protected inside a waist tuck (discussed below) at about the halfway point in the height of the tunic. See Kwaspen, 63 (Figure 3) for an illustration of this construction. The two smaller rectangles would be attached in the same way, but the waist tuck would be higher up — closer to 2/3 the height of the tunic. For more diagrams of how the smaller rectangle type was woven, see Mossakowska-Gaubert, 322 Figure 4; and Rooijakkers, 201.

Tunics woven in a single piece might also have fringe at the selvedge, but they would not need to be cut into pieces and sewn together. I chose to use the single-piece method simply because I had a sufficient length of fabric to do so, as these methods would result in the same finished look. However, because I used modern linen, my tunic has the warp edges at the bottom rather than along the sides. As a result, I folded the hem over to the outer side and sewed a row of fringe over it (see forthcoming fringe post).

Reinforcement:

Several reinforcing features were woven directly into the fabric. The top and bottom edges of the weaving (warp edges) had to secure the warp in some way. Some weavers used a twined edge where they started weaving and a braided edge where they ended. Alternatively, some weavers finished the warp edges as a fringe.

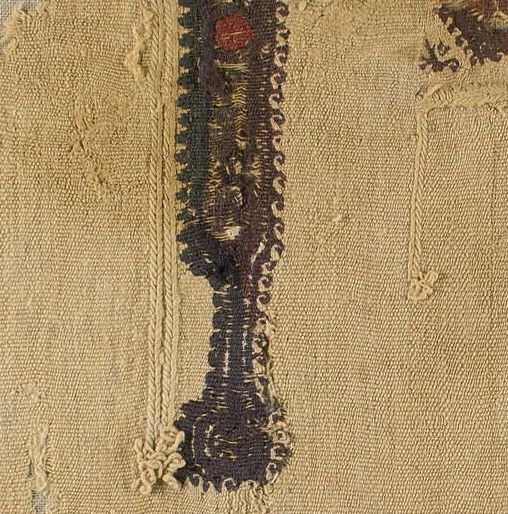

Many tunics also show lines of weft twining in locations where supplemental warps are needed for reinforcement and/or spots likely to be subject to higher stress and/or multidirectional pulling. See Kwaspen, 63 and Figure 5 at 64. These lines are found in both the background color and contrasting colors. Typically, they are paired with a second row twisting in the opposite direction, likely to keep the twist balanced in the fabric. The result is a double line of twisted threads that looks very similar to an applied braid or a line of compressed chain stitch embroidery.

Since my fabric was not actually woven with twined edging and had to be cut to shape from modern fabric, I created a cord for this edging by plying strands of linen weaving thread together and sewed it onto the sides of the tunic to mimic a twined warp cord. Sewing a cord onto fabric edges where they are missing a finish is a period technique documented in Kwaspen’s Reconstuction of a Deconstructed Tunic (page 66, under “Sleeves”).

Additionally, since I was working with fabric that was already woven, I used chain stitch to create lines of reinforcement along the edges near the armpit. I think a shorter stitch length would give a better looking result, but it does the job.

Waist Tuck (shaping):

Since woven fabric took a lot of effort to create, the tailoring techniques used to fit tunics to their wearer tended toward making folds and sewing them down to avoid cutting the fabric. This made it possible to unfold the fabric and re-fit it later if a person changed size or the garment was given to someone else. Rather than cutting and hemming the bottom of the garment, the fabric was tucked at the waist to achieve the desired length and then sewn in place. For discussion of recognizing opened waist tucks by finding banded areas with less discoloration, see Kwaspen, 64.

Based on a survey of extant pieces in digitized museum catalogues, it appears these tucks were often not of uniform depth along the entire waist; some exhibit deeper tucking on the sides than in the center, but few are deeper in the center than on the sides. Here are just a handful of examples at different heights and depths:

The uneven tucks may be due to body shape, or possibly the way the sides of the tunic drape past the shoulders so that they are not held up as high as the center of the body when being worn. My tunic ended up needing a deeper tuck in the middle and less tucking at the sides to get a relatively level hem when worn.

It is possible that a level hem is not the desired outcome, and I should make the tuck deeper on the sides. I will need to wear it more to determine whether this is the case.

References:

1. South, Kristin, and Anne Kwaspen. “The Tunics of Fag El-Gamus. A Survey of Types.” Proceedings of Purpureae Vestes VII. Redefining Textile Handcraft Structures, Tools and Production Processes, January 1, 2021. https://www.academia.edu/57096151/The_tunics_of_Fag_el_Gamus_A_survey_of_types.

2. Rooijakkers, Tineke. “New Styles, New Fashions: Dress in Early Byzantine and Islamic Egypt (5th-8th Centuries).” New Themes, New Styles in the Eastern Mediterranean: Christian, Jewish, and Islamic Encounters (5th-8th Centuries), January 1, 2017. https://www.academia.edu/9112805/New_Styles_New_Fashions_Dress_in_Early_Byzantine_and_Islamic_Egypt_5th_8th_Centuries_.

3. Mossakowska-Gaubert, Maria. “Tunics Worn in Egypt in Roman and Byzantine Times: The Greek Vocabulary.” Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD, January 1, 2017. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/texterm/20.

4. Kwaspen, Anne. “Reconstruction of a deconstructed tunic.” Published in Maria Mossakowska-Gaubert, ed., Egyptian Textiles and Their Production: ‘Word’ and ‘Object,’ (Hellenistic, Roman and Byzantine Periods) 2020. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/zeabook/86.